Let’s talk about language. And respect.

We humans haven’t been treating our environment well. I think at this point this is an undisputed fact rather than a bold opinion. In Australia, my home country, the mining industry and large-scale cattle farming alone have caused irreversible damage to the unique biosphere of the red continent.

However, as established in our previous blog post, the goal of this blog is not to have yet another discussion about the negative impact of industry on the environment. So let’s talk about language for a change. I’m not talking about any Western language, seeing that most of them have massively evolved over the centuries. Adapted so much to the change we were causing to our surrounding that we probably wouldn’t be able to understand an English-speaker from a mere 300 years ago. Instead, I am talking about some of the oldest languages on earth – Australian Aboriginal languages.

It has been estimated that at the time of the first European settlers’ arrival in 1788, around 200 distinct languages were spoken on the continent. 220 years later, more than half of these have been lost for ever. This is tragic in many ways, I think there is no need to emphasise how detrimental this is to Aboriginal communities, because no white woman such as myself can do the tragedy justice. Identity, history, culture, and traditions as well as the knowledge of the land, which is so essential to the First Nations People, are just a few of the victims of this loss of language. Let alone the non-language related acts of genocide performed against the traditional owners of Australia.

As Ms Amelia Turner, speaking on behalf of the Lhere Artepe Aboriginal Corporation put it: “The land needs words, the land speaks for us and we use the language for this. Words make things happen—make us alive. Words come not only from our land but also from our ancestors. Knowledge comes from Akerre, my own language and sacred language. Language is ownership; language is used to talk about the land.”

Interestingly, analysis of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) data shows positive associations between language use, wellbeing and socio-economic variables. This means if Indigenous communities are able to speak and are taught their traditional languages, they have e.g. lower rates of alcoholism, better physical and mental health.

Not only does this give hope for exiting the vicious circle of demographic and economic oppression the communities are trapped in, it also gives us non-Indigenous people hope. Why? Because language also means respect.

I think in order to explain this, we’ll have to take a quick detour to Aboriginal philosophy. Bear with me.

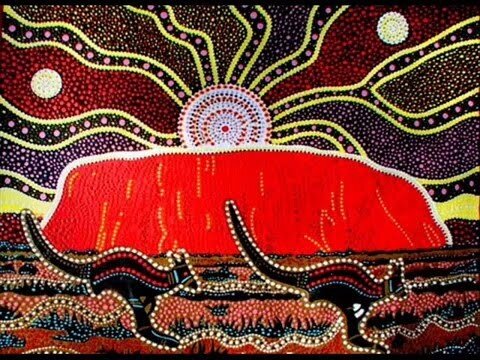

The Dreaming is indeed more of a philosophy, a way of life, rather than a religion. It is based on the inter-relation of everything – the land, the people, animals, and plants. Most of the stories and songs about the time when the Spirit Ancestors roamed the land have been passed down for hundreds of years. They explain the origins of the universe and function as – this is a very Western translation – a map of the country, which describes the characteristics, the water and food sources in a certain area. Every inch of Australia is written in song, every rock formation or bowing tree a witness to the first feet to walk along the land.

This deep connection to the land creates a heavily engrained mutual respect between human and nature. The people take as much as they need, shape the earth to the extent necessary and help nature flourish. In turn, the land gives them everything from bushberries to kangaroos.

When European settlers came and took the land, they not only deprived the native populations of the foundation of their existence (their country), but with it they took words and names for mountains, rivers, and trees. Uluru became Ayers Rock, Kata Tjuta became the Olgas and Gawula became Mount Wheeler. Not only were these the names of colonists who had in some cases been involved in horrific acts of violence towards the Indigenous communities, the new names also stole the thousand-year history between the peoples and the land.

There have been recent attempts to “give back” the stolen land to the traditional owners and e.g. the government of Queensland has renamed Mount Wheeler back to Gawula as an act of reconciliation. Malcolm Mann of the Darumbal Aboriginal Corporation welcomed this but emphasized that Gawula has always been the mountain’s name to his people, so not much is changing. However, it “does show a move away from a fairly traumatic past.”

I am certain that giving back the traditional names to landmarks in Australia will not just improve the relations between white Australians and Aboriginal communities, but also restore some of the respect for the land. Uluru, the famous and sacred red rock in the centre of the continent, for example, has been closed for climbers for just over a year now, which was a huge success for the traditional owners, the Anangu people.

To be sure, these are baby steps we are taking. And at the rate these acts of reconciliation are taking place, the planet will have already died by the time all the land has been fully returned to its traditional owners. Nonetheless, I believe that the symbolism of these acts is something us Westerners urgently need to learn from.

BY Kelly Bebendorf (Australia) | CLASS OF 2021