A new look at thyroid diseases

(Source: Constructor University)

Thyroid disorders are frequently found in about one-third of the adult population in Germany. In a research project of the German Research Foundation (DFG), scientists at Jacobs University are asking how the healthy thyroid works. Their findings might help adapting diagnosis and therapy of thyroid diseases.

The little butterfly-shaped organ is a powerhouse. A thyroid that releases too much or too little hormone can trigger a wide variety of health problems: For example cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, morbid obesity, or immune diseases. The organ can also play a role in depression. “The importance of a healthy thyroid has been known for more than 100 years. All the more astounding that there are some aspects about the functioning of this organ and its interaction with other organs that are still unknown,” says Klaudia Brix, Professor of Cell Biology at Jacobs University. She and her team now hope to close some of these gaps in knowledge. “Thyroid Trans Act” is the DFG-supported priority program SPP 1629 coordinated by Klaudia Brix at Jacobs University, Professor Heike Biebermann at the Charité in Berlin, and Professor Dagmar Führer at the Essen University Medical Center. A total of 18 research institutes throughout Germany are participating.

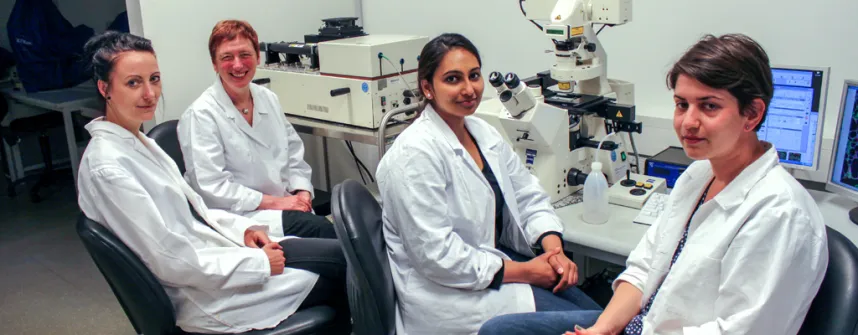

“We come from very different research institutions, but we have the same goal: We want to understand better how the thyroid functions. That connects us,” says Vaishnavi Venugopalan, one of the young scientists on the project team at Jacobs University. “The collaboration with other research institutions is really good,” adds her colleague Maren Rehders. “It is a very open, collegial exchange, without any competition thinking.”

Like other research teams at Jacobs University, the thyroid researchers also comprise an international community: Vaishnavi Venugopalan comes from India, Maren Rehders and Klaudia Brix from Germany, their colleagues Maria Qatato and Joanna Szumska from Palestine and Poland. An intercultural team in an interdisciplinary research community pursuing complex problems. “It is exciting to do research in such an environment, and on a topic that is important to so many people,” says Maria Qatato.

The researchers are focusing particularly on the so-called thyroid hormone transport molecules. “For a long time, it was believed that the thyroid hormones simply diffuse from the circulatory system into the cells of individual target organs,” explains Klaudia Brix. In the meantime, we know that the route of uptake into the cells is substantially more complex. Because there are transport proteins in the cell membrane. They ensure that the hormones get into the respective target cells, or that they can be released from the thyroid cells into the blood. An impaired function of these thyroid hormone transport proteins can have major effects on health.”

This finding is approximately 15-years old finding, and it has led to new scientific interest in the thyroid gland. “The important notion here is not just the question of how many hormones the thyroid produces but also how they are taken up at the destination, meaning by the cells of the respective thyroid hormone target organ. Our approach is therefore not to consider the thyroid in isolation but also to get a better understanding of those cell functions that are directed by thyroid hormones.”The complexity of the interactions among the thyroid and the metabolism of the body are shown, for example, by the thyronamines. These are molecules derived from the classical thyroid hormones. They are generated from the thyroid hormones by specific biochemical processes. In human organs, the derivatives resulting from such transformation processes may exert effects that are opposite to those of the classic thyroid hormones. For instance, a hormone that leads to elevated blood pressure, may in some circumstances have as a counterpart a thyronamine that lowers blood pressure. Brix speaks of a precision regulated balance. “Like in a scale.”

What does it mean for people, when this balance no longer exists? The researchers at Jacobs University are confident that the discovery of thyronamines can lay the cornerstone to a better understanding of some metabolic pathways. But they also know that these are part of complex interrelationships. “Before we can think about new drugs, we have to understand even better the concentration and precise composition of the thyronamines in the body,” says Klaudia Brix. “We are convinced: The better we succeed in doing so, the more it will be possible to provide targeted therapy to people with thyroid disorders. That prospect, in particular, is motivating.“

Additional information:

http://www.thyroidtransact.de/http://brixgroup.user.jacobs-university.de/https://www.jacobs-university.de/directory/kbrix

Questions will be answered by:

Prof. Dr. Klaudia Brix| Professor of Cell Biologyk.brix [at] jacobs-university.de | Tel.: +49 421 200- 3246