Researchers at Jacobs University examine children’s trust in social robots

April 08, 2021

They are not intended to replace teachers, but to support them – for example, through personalized learning tasks tailored to the needs of each individual child. Social robots that communicate, interact, and build relationships with humans are increasingly being tested in school education, but what factors influence whether children actually trust these robots as teachers? That is what researchers at Jacobs University and at Uppsala University investigated in a joint meta-analysis.

"As the role of robots in education becomes a reality, we need to better understand how these machines can improve their teaching, how they are perceived by the children, and how children relate to them," said Professor Arvid Kappas, Dean and psychology professor at Jacobs University.

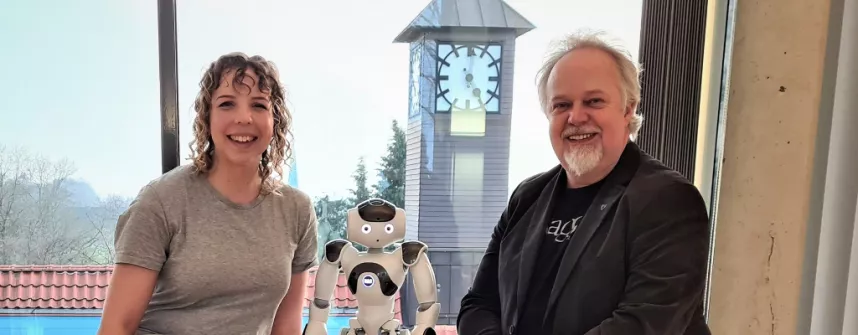

To contribute to a better understanding of this future-oriented issue, he and Rebecca Stower, research associate at Jacobs University, worked together with Natalia Calvo-Barajas and Professor Ginevra Castellano from Uppsala University in Sweden. They conducted a joint meta-analysis on children's trust in social robots.

A meta-analysis systematically evaluates existing scientific research on a given topic. The researchers examined 414 studies published on trust in child-robot-interaction so far. A distinction was made between two types of trust: On the one hand, social trust in the robot as a kind of friend with whom an emotional bond is established. And on the other, trust in the robot’s competencies: Can the robot successfully complete the tasks assigned to it?

Furthermore, they investigated the effects of the robot's design and its social behaviors on trust formation. Most of the robots studied resemble humans, utilizing gaze cues or imitating gestures and speech. Consideration was also given to how errors made by the robot are perceived and if they have repercussions on the trust relationship.

"Our meta-analysis shows that the assumption that robots should resemble humans as much as possible is not necessarily true," Stower explained. "Robots are robots; more human-like attributes can actually lead to lower confidence in the robot’s competence." The development of future robots should therefore focus less on how to design a perfect robot, but rather on how it can best perform the attributed task. "Robots make mistakes, sometimes their voice recognition fails or they fall over. My observation is that children are actually very tolerant of robots making mistakes," said Stower, who is in the final year of her PhD at Jacobs University in which she is researching children's trust in social robots.

The meta-analysis was funded as part of the European Union-funded research program "ANIMATAS," which promotes intuitive human-machine interaction with human-like social skills for school education. Jacobs University is the only German university to be part of the international consortium of researchers.

Link to the study:

Rebecca Stower, Natalia Calvo-Barajas, Ginevra Castellano, Arvid Kappas: A Meta-analysis on Children’s Trust in Social Robots, International Journal of Social Robotics

Questions are answered by:

Rebecca Stower

Research Associate, PhD Student

Tel: +49 421 200-3405

Email: r.stower [at] jacobs-university.de